Preguntas humanas - Respuestas cósmicas

RUDOLF STEINER

VII conferencia

Dornach 8 de julio de 1922

He hablado de Franz Brentano con cierta extensión porque el hecho es inmediatamente evidente de que la primera obra de este importante filósofo, publicada por sus estudiantes de su estado, fue una obra sobre la vida de Jesús, la enseñanza de Jesús. Eso proporcionó el punto de contacto externo. Pero quería algo más profundo con la presentación de la vida de este filósofo. Quería mostrar, a través de una persona que no era solo un pensador, no solo un científico, sino que era verdaderamente un buscador de la verdad como un ser humano completo, cómo una personalidad de este tipo tenía que posicionarse en la vida espiritual de la segunda mitad del siglo XIX.

Franz Brentano nació en 1838, por lo que era un estudiante en el mismo momento en que la mentalidad científica estaba surgiendo dentro de la civilización moderna. Era un estudiante que, como ha visto, era un católico devoto que, como católico devoto, se aferraba firmemente al mundo espiritual, pero solo de la manera que era posible desde la práctica religiosa católica y la "teología" católica. Este hombre, que había crecido así en una cierta comprensión evidente del mundo espiritual, de la inmortalidad del alma, de la existencia de Dios, etc., lo hizo como científico, y de hecho como el científico más concienzudo imaginable, en la era en que el pensamiento científico lo significaba todo. De modo que, más que con cualquier otra personalidad, cuando uno está familiarizado con Franz Brentano, tiene la sensación de que aquí hay una persona de profunda espiritualidad que, sin embargo, frente a la actitud científica del siglo XIX, no se elevó a ella, no pudo penetrarla en una comprensión real de la vida espiritual. En realidad, no conozco ninguna personalidad en los tiempos modernos en la que la necesidad de la visión antroposófica del mundo surja de manera tan característica. En el caso de Franz Brentano, uno quisiera decir: en realidad solo necesitaba dar uno o dos pasos más y estaba con la antroposofía. No vino a ello porque quisiera mantener lo que era una práctica científicamente común. Franz Brentano, precisamente por lo que describí ayer como la característica de su personalidad, incluso en su apariencia externa, a través de la dignidad de su comportamiento, a través de la seriedad que estaba presente en todo lo que pronunciaba, ya da la impresión de que podría haberse convertido en una especie de personalidad principal en la segunda mitad del siglo XIX.

Ahora puede preguntar con razón: ¿Pero cómo es que esta personalidad ha permanecido completamente desconocida en los círculos más amplios? Franz Brentano en realidad se dio a conocer solo a un estrecho círculo de estudiantes. Todos estos estudiantes son personas que recibieron la inspiración más profunda de él. Esto todavía se puede ver en el trabajo de aquellos que son a su vez los estudiantes de esos estudiantes, porque son ellos los que todavía están presentes hoy. Franz Brentano causó una impresión significativa en un círculo estrecho. Y la mayoría de los estudiantes de este círculo están ciertamente tan inclinados hacia él que lo perciben como una de las personas más estimulantes y significativas de los últimos siglos.

Pero el hecho de que Brentano haya permanecido desconocido en los círculos más amplios es característico de todo el desarrollo de la civilización en el siglo XIX. Se podría, por supuesto, citar a muchas personalidades que, en una dirección u otra, también son representantes de la vida intelectual en el siglo XIX. Pero no podías encontrar una personalidad tan significativa y característica como Franz Brentano, por mucho que miraras. Por lo tanto, me gustaría decir: Franz Brentano muestra que aunque la ciencia natural, en la forma que tomó en el siglo XIX, puede adquirir una gran autoridad, no puede ejercer un liderazgo espiritual dentro de toda la cultura a pesar de esta gran autoridad. Para eso, la ciencia natural debe desarrollarse primero en ciencia espiritual; entonces tiene todo lo que puede verdaderamente, junto con la ciencia espiritual, asumir un cierto liderazgo en la vida espiritual de la humanidad.

Para entender esto, hoy debemos tener una visión más amplia. Si miramos hacia atrás a los primeros tiempos de la humanidad, sabemos que una especie de clarividencia onírica estaba presente en todas partes como una facultad humana general. A esta clarividencia onírica, los iniciados, los iniciados de los misterios, añadieron un conocimiento suprasensible superior, pero también un conocimiento sobre el mundo sensorial.

Si nos remontáramos a los primeros días del desarrollo humano, no encontraríamos ninguna diferencia en la forma en que se trata lo físico y lo suprasensible. Toda la vida espiritual ha procedido de las escuelas de misterios, que eran básicamente iglesias e instituciones artísticas al mismo tiempo. Pero en el sentido más profundo, esta vida espiritual influyó en toda la vida humana en los viejos tiempos, incluida la vida estatal y económica. Los que estaban activos en la vida estatal buscaban el consejo de los sacerdotes de misterio, pero también lo hacían los que querían dar impulso a la vida económica. En realidad, no había separación entre los elementos religiosos y científicos en aquellos tiempos antiguos. Los líderes de la vida religiosa eran los líderes de la vida intelectual en general y también eran las personas que marcaban la pauta en las ciencias. Pero cada vez más, el desarrollo de la humanidad se ha formado de tal manera que las corrientes de la vida humana que originalmente formaban una unidad se han separado. La religión se ha separado de la ciencia, del arte.

Esto sucedió solo lenta y gradualmente. Si miramos hacia atrás a Grecia, encontramos que no había ciencia natural en nuestro sentido, y junto a ella, por ejemplo, filosofía; más bien, la filosofía griega también discutía las ciencias naturales, y no había una ciencia natural separada. Pero como la filosofía en Grecia surgió como algo independiente, el elemento religioso ya se había separado de esta filosofía. Aunque los misterios seguían siendo la fuente de las verdades más profundas, en Grecia, especialmente en la Grecia posterior, lo que daban los misterios ya estaba siendo criticado desde el punto de vista de la razón filosófica. Pero la revelación religiosa continuó, y cuando apareció el Misterio del Gólgota, fue esencialmente la revelación religiosa la que se propuso comprender este misterio. Cualquier comprensión de la teología que todavía existiera dentro de la civilización europea durante los primeros siglos ya no es comprendida adecuadamente por la gente de hoy; se refieren a ella despectivamente como "gnosis" y cosas por el estilo. Pero había una gran cantidad de comprensión espiritual en esta gnosis, y había una clara conciencia de que uno debe entender los asuntos espirituales de la misma manera que uno entiende hoy, por ejemplo, la gravedad o los fenómenos de la luz o cualquier otra cosa en el sentido físico. No tenían la conciencia de que hay una ciencia separada de la vida religiosa. Incluso en suelo cristiano, los primeros padres de la iglesia, los primeros grandes maestros del cristianismo, estaban absolutamente convencidos de que estaban tratando el conocimiento como algo unificado. Por supuesto, la separación griega de la vida religiosa ya estaba allí, pero incluían tanto la contemplación de lo religioso como la contemplación racional de lo meramente físico en el tratamiento de todos los asuntos espirituales. Fue solo en la Edad Media que esto cambió. En la Edad Media surgió la escolástica, que ahora hacía una estricta separación -como ya señalé ayer- entre la ciencia humana y lo que es el conocimiento real de lo espiritual. Esto no podría lograrse mediante la aplicación de poderes humanos independientes de conocimiento; solo podía alcanzarse a través de la revelación, a través de la aceptación de las revelaciones. Y cada vez más se había llegado a decir que uno decía: El hombre no puede penetrar en las verdades más elevadas a través de sus propios poderes de conocimiento; Debe aceptarlos tal como son entregados por la iglesia como revelación. La ciencia humana solo puede extenderse sobre lo que dan los sentidos y sacar algunas conclusiones de lo que los sentidos dan como verdades, como dije ayer.

Thus, a strict distinction was made between a science that spread over the sensory world and that which was the content of revelation. Now, for the development of modern humanity, the last three to five centuries have become extraordinarily significant in many respects. If you had told a person from those older times, when religion and science were one, that religion was not based on human knowledge, he would have considered it nonsense; for all religions originally came from human knowledge. Only it was said: If man confines himself to his consciousness, as it is given to him for everyday life, then he does not attain to the highest truths; this consciousness must first be raised to a higher level. From the old point of view, it was said just as one is forced to say today, for example, according to what I have presented in my book “How to Know Higher Worlds” and in the second part of my “Occult Science in Outline”: that man must ascend through special treatment of his soul abilities in order to gain higher knowledge. This was also said in ancient times. People were aware that with ordinary consciousness one can only recognize what is spread around man; but one can further develop this consciousness and thus arrive at supersensible truths. Thus in those ancient times one would not have spoken of a revelation reaching man somewhere without his own activity. That would have been felt to be nonsense. And so all the dogmas contained in the various church teachings originally come from such initiation truths. Today, people easily say: dogmas such as the Trinity or the Incarnation must have been revealed, they cannot be approached through human cognitive abilities. But originally they did arise out of human cognitive abilities.

And in the Middle Ages, people had progressed to a greater use of their intellect. This is characteristic, for example, of scholasticism, in that the intellect was used in a grand sense, but only applied to the sensual world, and that at this stage of human development one no longer felt capable of developing higher powers of cognition, at least not in the circles in which the old dogmas had been handed down as doctrines of revelation. Then they refused to pave the way for man to the supersensible world through higher powers of knowledge. So they took over what had been achieved in ancient times through real human knowledge, through tradition, through historical tradition, and said that one should not examine it with human science.

People gradually came to accept this attitude towards knowledge. They gradually got used to calling belief that which was once knowledge, but which they no longer dared to attain; and they only called knowledge that which is actually gained through human cognitive abilities for the sensual world. This doctrine had become more and more pronounced, especially within Catholicism. But as I already told you yesterday: basically, all modern scientific attitudes are also nothing more than a child of this scholasticism. People just stopped at saying that the human intellect could only gain knowledge about nature, and did not care about the supersensible knowledge. They said that man could not gain this through his abilities. But then it was left to faith to accept the old knowledge as handed-down dogmas or not.

After the 18th century had already proclaimed mere sensual knowledge and what can be gained from it through rational conclusions, the tendency emerged in the 19th century in particular to only accept as science what can be gained in this way by applying human abilities to the sensual world. And in this respect, the 19th century has achieved an enormous amount, and great things are still being achieved in the field of scientific research through the application of scientific methods.

I would like to say that the last public attempt to ascend into the spiritual world was made at the turn of the 18th to the 19th century by the movement known as German idealism. This German idealism was preceded by a philosopher like Cart, who now also wanted to express the separation between knowledge and belief philosophically. Then came those energetic thinkers, Fichte, Schelling, Flegel, and these stand there, at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th century, like last mighty pillars, because they wanted to go further with the human capacity for knowledge than mere sensory knowledge and what can be deduced from it.

Fichte, Schelling and Hegel are very different from one another. Fichte started from the human ego, developed an enormous power precisely in grasping the human ego, and sought to conquer the world cognitively from the human ego. Schelling developed a kind of imaginative construction of a world view. This impetus in the imaginative construction of thoughts even brought him close to an understanding of the mysteries. Hegel believed in the thought itself, and he believed that in the thought that man can grasp, the eternal lives directly. It is a beautiful thought when Hegel said that he wanted to recognize the spirit and conquer it from the point of view of thought. But only those who grasp Hegel's general striving, this striving towards the spirit, can really taste him. For when one reads Hegel — most people soon stop reading, after all — he is, despite his belief in the spirituality of thought, a terribly abstract thinker when he expounds his ideas. And it is true that, although the impulse that lived in Hegel in terms of the spirit was an immensely strong one, Hegel gave mankind nothing but an inventory of abstract concepts.

Why was that so? It is indeed a tremendous tragedy that these robust, powerful thinkers, Fichte, Schelling, Hegel, did not actually penetrate to spirituality.

This is because, in the general civilization of that time, humanity was not yet mature enough to really open the gates to the spiritual world. Fichte, Schelling and Hegel only got as far as thought. But what is the thought that lives in man in ordinary consciousness?

Do you remember what I said some time ago? When we follow a person's life from birth to death, we have the person before us as a living being; soul and spirit warm and illuminate what stands before us as a physical being. When the person has died for the physical world, then we have the corpse in the physical world. We bury or cremate this corpse. Just think what a tremendous difference there is for an unprejudiced human observer of life between a fully living human being and a corpse. If you can only grasp this difference with your heart, then you will be able to understand what the spiritual scientist has to say about another phase of life, when man is considered between death and a new birth, as he is as a soul-spiritual being in a spiritual world, how he develops there, how he, while growing old here on earth, becomes younger and younger in the spiritual world until the moment when he finds his way down to a physical embodiment. What lives in man can be grasped just as much with the higher spiritual powers as one can grasp what lives in a physical human being. And then one can ask oneself: What remains of it when the human being has been born, what presented itself to our view in the spiritual world above, before the soul-spiritual descended? What remains in the human being, perceptibly, are his thoughts. But these thoughts, which the human being then carries within himself here on earth through the physical body, are the corpse of the thoughts that belong to the human being when he lives between death and a new birth in the spiritual and soul world. The abstract thoughts we have here are quite a corpse compared to the living being that is in man between death and a new birth, just as the corpse is in the physical compared to the living person before he has died for the physical world.

Those who do not want to take the step of enlivening abstract thoughts allow nothing more to live in them than the corpse of what was in them before they descended to earth. And only this corpse of thoughts lived in Fichte, Schelling and Hegel, however magnificent these thoughts are. One would like to say: In ancient times, when religion, science and art were still one, something of the life that belongs to man in the spiritual world still lived on in earthly thoughts. Even in Plaio, one can perceive in the sweep of his ideas how something supermundane lived on in him. This is becoming less and less. People keep the knowledge of the supermundane as revelation. But otherwise the human being would not have been able to become free, he would not have been able to develop freedom. The human being comes more and more to have nothing but the corpse of his prenatal inner life in his thinking. And just as one sometimes finds in certain people, when they have died, an enormous freshness in the corpse for a few days, so it was with the corpse-thoughts of Fichte, Schelling and Hegel: they were fresh, but they were nevertheless just those corpses of the supersensible, of which a real spiritual science must speak.

But I ask you now: Do you believe that we could ever encounter a human corpse in the world if there were no living people? Anyone who encounters a human corpse knows that this corpse was once alive. And so someone who really looks at our thinking, our abstract, our dead, our corpse thinking, will come to the conclusion that this too once lived, namely before man descended into a physical body.

But this realization had also been lost to man, and so people were experiencing dead thinking, and they revered everything that came to them from living thinking as a revelation, if they still placed any value on it at all. This was particularly confirmed by the great advances in natural science that came in the period I have already mentioned, when Franz Brentano was young.

To the many peculiarities of Franz Brentano, I must add two more today. Yesterday I wanted to characterize the personality more, today I want to point out the development over time. Therefore, today's consideration must be somewhat more general.

In addition to all the qualities that I mentioned yesterday about this Franz Brentano, who grew out of Catholicism but then became a general philosopher, he had an immense antipathy towards Fichte, Schelling and Hegel. He did not rail against them as Schopenhauer did, because he had a better education; but he did use harsh words, only more delicately expressed, not in the same truly abominable tone as Schopenhauer's. But one must realize that a man who grows out of Catholicism into a new outlook cannot, after all, have any other attitude toward Fichte, Schelling and Hegel than Franz Brentano had. When one has outgrown scholasticism, one wants to apply to the sense world what for Hegel, for example, is the highest human power of cognition, thinking, and in the sense world, thinking is only an auxiliary means.

Just think: with this thinking-corpse one approaches the sense world, one grasps inanimate nature first. You cannot grasp living nature with this thinking anyway. This thinking corpse is just right for inanimate nature. But Hegel wanted to embrace the whole world with all its secrets with this thinking corpse. Therefore, you will not find any teaching about immortality or God in Hegel, but what you do find will seem quite strange to you.

Hegel divides his system into three parts:

logic, natural philosophy, and the doctrine of the spirit = art, religion, science

Logic is an inventory of all the concepts that man can develop, but only of those concepts that are abstract. This logic begins with being, goes to nothingness, to becoming. I know that if I were to give you the whole list, you would go crazy because you would not find anything in all these things that you are actually looking for. And yet Hegel says: That which emerges again in man when he develops being, nothingness, becoming, existence and so on as abstract concepts, that is God before the creation of the world.

Take Hegel's logic, it is full of abstract concepts from beginning to end, because the last concept is that of purpose. You can't do much with that either. There is nothing at all about any kind of soul immortality, about a God in the sense that you recognize it as justified, but rather an inventory of nothing but abstract concepts. But now imagine these abstract concepts as existing before there is nature, before there were people, and so on. This is God before the creation of the world, says Hegel. Logic is God before the creation of the world. And this logic then created nature and came to self-awareness in nature.

So first there is logic, which, according to Hegel, is the god before the creation of the world. Then it passes into its otherness and comes to itself, to its self-awareness; it becomes the human spirit. And the whole system then concludes with art, religion and science as the highest. These are the three highest expressions of the spirit. So in religion, art and science, God continues to live within the earth. Hegel registers nothing other than what is experienced on earth in everyday life. He actually only proclaims the spirit that has died, not the living spirit.

This must be rejected by those people who seek science in the modern sense, based on a scientific education. It must be rejected because, when one penetrates into nature with dead concepts, the matter does not go so that one remains with the abstractions. Even if you are so poorly educated in botany that you transform all the beautiful flowers into the number of stamens, into the description of the seed, the ovary and so on, even if you have such abstract concepts in your head, and then go out with a botany drum and bring back nothing but abstract concepts, at least the withered flowers are still there, and they are still more concrete than the most abstract concepts. And when you, as a chemist, stand in the laboratory, no matter how much you fantasize about all kinds of atomic processes and the like, you cannot help but also describe what happens in the retort when you have a certain substance inside and below it the lamp that causes this substance to evaporate, melt and so on. You still have to describe something that is a thing. And finally, when physicists in optics also draw for you how light rays refract and describe everything that light rays still do according to the physicists, you will still be reminded of colors again and again when that beautiful drawing is made that shows how light rays pass through a prism, are deflected in different ways. And even if all color has long since evaporated in the physical explanation of color, you will still be reminded of the colors. But if you want to grasp the spiritual with a completely abstract system of concepts and with completely abstract logic, then you have no choice but to use abstract logic. A person like Franz Brentano could not accept this as a real description of the spirit, nor could the other scholastics, because at least they still have tradition as revelation. Therefore, as a student in the mid-19th century, Brentano was faced with a truly irrepressible thirst for truth and knowledge, with an inner scientific conscientiousness that was unparalleled in his time, so that he could not receive anything from those who were still the last great philosophers of modern civilization. He could only accept the strict method of natural science. In his heart he carried what Catholicism with its theology had given him. But he could not bring all this together into a new spiritual understanding.

But what is particularly appealing is how infinitely truthful this human being was. Because – and this brings me to the other thing I mentioned – when we look at the human being as he is born into the physical world, as he makes his first fumbling movements as a child, as we first fumbling movements as a child, we see in an unskillful way the unfolding of what was tremendously wise before it descended into the physical world. If we understand spiritual science correctly, we say to ourselves: We see how the childlike head organism is born. In it we have an image of the cosmos. Only at the base of the skull do the earthly forces, as it were, brace themselves. If the base of the skull were rounded, as the top of the head is rounded, the head would truly be a reflection of the cosmos. This is something that human beings bring with them. We can certainly regard the head, when we consider it as a physical body, as a reflection of the cosmos. This is truly the case.

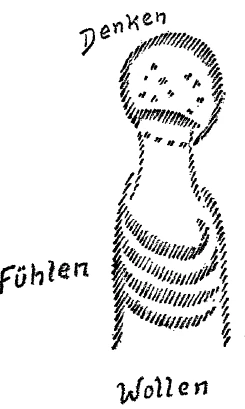

I was criticized for mentioning an important fact in public, but without mentioning such facts, one cannot actually get to the world's interrelations: I have publicly stated that there is a certain arrangement of furrows in the human brain, certain centers are and so on. Even in these smallest details, this human brain is a reflection of the starry sky at the time when the person is born. In the head we see an image of the cosmos, which we also see externally with our senses, even though most people do not perceive its spiritual aspect. In the chest organism, in what mainly underlies the rhythmic system, we see how the roundness of the cosmos has already been somewhat overcome by adapting to the earth. But if you follow the chest organism with its peculiar formation of the spine with the ribs and sees how this thoracic organism is connected to the cosmos through breathing, then, even if only in a very altered form, something like an image of the cosmos can still be seen in the thoracic, in the rhythmic organism. But no longer in the metabolic-limb organism. There you cannot possibly see anything that is modeled on the cosmos. Now, the formation of the head is connected with thinking, the thoracic organism, the rhythmic organism with feeling, and the metabolic-limb organism with will.

¿Por qué es precisamente el organismo metabólico de las extremidades, que en realidad es la parte más terrenal del ser humano, el que es el asiento de la voluntad? Así es como está conectado: en la cabeza humana tenemos una imagen muy fiel del cosmos. El alma-espiritual ha fluido hacia la cabeza, hacia las fuerzas formativas. Se podría decir que el ser humano aprendió de las fuerzas cósmicas antes de descender a la tierra y formó su cabeza en consecuencia. Todavía forma un poco el organismo torácico, pero ya no el organismo de la extremidad en absoluto. La voluntad está en este último. De modo que cuando uno mira el organismo externo humano, el pensamiento debe asignarse a la cabeza, el sentimiento al hombre intermedio y el deseo al organismo metabólico de las extremidades. Pero en lo que es realmente lo más bajo, el metabolismo y las extremidades, lo espiritual también se mantiene mejor, de modo que en nuestro pensamiento solo tenemos un cadáver de lo que éramos antes de descender. En nuestros sentimientos tenemos un poco más, pero el sentimiento, como sabes, permanece en un estado de ensueño, y la voluntad, ya ni siquiera se nota con la conciencia ordinaria. La voluntad permanece enteramente en el inconsciente, pero en ella todavía hay la mayor parte de la vida de lo que éramos antes de descender a la tierra. Cuando nos desarrollamos como niños, la mayor parte de nuestra alma inmortal está en nuestra voluntad. Ahora, la mayoría de la gente no tiene muchos escrúpulos; dicen: El hombre tiene los tres poderes del alma dentro de él, pensar, sentir y querer. Sabes, estas tres actividades del alma se enumeran como si estuvieran presentes para la conciencia ordinaria, mientras que en la antroposofía primero tenemos que señalar que en realidad solo el pensamiento está completamente despierto. El sentimiento ya es como los sueños en las personas, y la gente no sabe nada en absoluto sobre la voluntad. Debo enfatizar una y otra vez: incluso si solo queremos levantar un brazo, el pensamiento, "estoy levantando mi brazo", fluye hacia el organismo y se convierte en voluntad, de modo que el brazo está realmente levantado. El hombre no sabe nada de esto, duerme a través de él en el estado de vigilia, al igual que duerme durante las cosas desde que se duerme hasta que se despierta. Entonces, en lugar de decir: tenemos en nosotros el pensamiento despierto, el sentimiento soñador, el querer dormir, dicen: tenemos pensamiento, sentimiento y voluntad, que se supone que están a la par entre sí.

Ahora imagina a una persona que tiene un sentido infinito de la verdad y que trabaja con la ciencia moderna, es decir, que solo usa el pensamiento. El científico natural moderno, ya sea que esté usando un microscopio, mirando el cosmos a través de un telescopio o haciendo astrofísica con un analizador espectral, siempre recurre solo al pensamiento consciente. Por lo tanto, se convirtió en un axioma para Franz Brentano que toda inconsciencia tenía que ser rechazada. Quería ceñirse solo al pensamiento consciente ordinario, y para ello no quería desarrollar habilidades cognitivas superiores. ¿Qué podríamos esperar realmente de una persona así cuando habla del alma, cuando quiere hablar como psicólogo? Uno podría esperar que no hablara de la voluntad en absoluto en psicología si se apega solo a la conciencia. Uno podría esperar que tachara el testamento por completo, que no estuviera seguro de los sentimientos y que realmente tratara solo el pensamiento correctamente.

Otras mentes más superficiales no han llegado a esto. La psicología de Franz Brentano no divide las facultades del alma en pensar, sentir y querer, sino en imaginar, juzgar y en los fenómenos del amor y el odio, es decir, en los fenómenos de la simpatía y la antipatía, es decir, del sentimiento. No encontrarás ninguna voluntad en él en absoluto. La voluntad activa correcta está ausente de la psicología de Brentano porque era un buscador completamente honesto de la verdad, y realmente tenía que admitir: simplemente no puedo encontrar la voluntad.

Por otro lado, hay algo tremendamente conmovedor en ver cuán infinitamente sincera y honesta es realmente esta personalidad. La voluntad está ausente de la psicología de Brentano, porque separa el juicio y la imaginación de modo que ahora tiene tres partes en la vida del alma; pero el juicio y la imaginación coinciden en términos de la capacidad del alma, de modo que en realidad solo tiene dos.Ahora considere la consecuencia de lo que aparece en Brentano. ¿Qué tiene en realidad i. en el hombre? Al convertirse en un científico natural moderno y no dar a nada un valor que no se presente al pensamiento consciente de acuerdo con el método científico natural, excluye la volición del alma humana. ¿Y qué elimina con ello? Precisamente lo que traemos con nosotros como seres vivos de nuestro estado antes de descender a un cuerpo físico.

Brentano se enfrentó a una ciencia que eliminaba precisamente lo eterno en el alma para él. Los otros psicólogos no sintieron esto. Lo sintió, y por lo tanto surgió para él el tremendo abismo entre lo que una vez fue una doctrina de revelación que le hablaba de lo eterno en el alma humana, y lo que podía encontrar solo de acuerdo con su método científico, que incluso cortó la volición y, por lo tanto, lo eterno del alma humana.

Por lo tanto, Brentano es una personalidad que es característica de todo lo que el siglo XIX no pudo dar a la humanidad. Las puertas al mundo espiritual tenían que abrirse. Y por eso les he hablado de Franz Brentano, que murió en Zurich en 1917, porque en él veo lo más característico de todos aquellos filósofos del siglo XIX que ya tenían una seria lucha por la verdad. que no quería elevarse a una comprensión espiritual del mundo, y de esta manera mostrar en todas partes que ha llegado el momento en que se necesita esta concepción espiritual. ¿Cuál es, después de todo, la diferencia entre lo que realmente quiere la ciencia espiritual en el sentido antroposófico y el esfuerzo trágico de un hombre como Franz Brentano? Que Franz Brentano, con tremenda perspicacia, ha traído los conceptos que se pueden obtener de la conciencia ordinaria, y dijo: Ahí es donde tienes que detenerte. Pero el conocimiento no es completo; uno se esfuerza en vano por el conocimiento real. Pero nunca estuvo satisfecho con eso; siempre quiso salir. Simplemente no podía salir de su ciencia natural. Y así se mantuvo hasta su muerte. Se podría decir que la ciencia espiritual tenía que comenzar donde Brentano lo dejó, tenía que dar el paso de la conciencia ordinaria a la conciencia superior. Por eso es tan extraordinariamente interesante, de hecho el filósofo más interesante de la segunda mitad del siglo XIX, porque en él la lucha por la verdad era realmente algo personal. Hay que decirlo: si quieres estudiar un síntoma de lo que una persona tuvo que experimentar en el desarrollo de la ciencia y en el desarrollo espiritual de los tiempos modernos, puedes considerar a este sobrino de Clemente Brentano, el filósofo Franz Brentano. Es característico de todo lo que una persona tiene que buscar y no puede encontrar con el método científico habitual. Es característico de esto porque uno debe ir más allá de lo que se esforzó con un sentido tan honesto de la verdad. Cuanto más de cerca se le mira, hasta las estructuras de su psicología, más se hace evidente. Es precisamente una de esas mentes que muestran: la humanidad necesita de nuevo una vida espiritual que pueda intervenir en todo. No puede provenir de las ciencias naturales. Pero esta ciencia natural es el destino de los tiempos modernos en general, ya que se ha convertido en el destino de Brentano. Porque, como el verdadero Fausto moderno del siglo XIX, Brentano se sienta primero en Würzburg, luego en Viena, luego en Florencia, luego en Zurich, luchando con los mayores problemas de la humanidad. No admite que "no podemos saber", pero tendría que hacerlo si fuera plenamente consciente de su propio método. De hecho, tendría que decirse a sí mismo: la ciencia natural es lo que me impide emprender el camino hacia el mundo espiritual.

Pero esta ciencia natural habla un lenguaje fuerte y autoritario. Y así es también en la vida pública de hoy. La ciencia en sí misma no puede ofrecer a las personas lo que necesitan para su alma. Los mayores logros de los siglos XIX y XX no pudieron dar a la gente una especie de espíritu guía. Y esta actitud científica es un fuerte obstáculo debido a su poderosa autoridad, porque dondequiera que aparece la antroposofía, la ciencia inicialmente se opone a ella, y aunque la ciencia misma no puede dar nada a la gente, cuando se trata de antroposofía, la pregunta es: ¿la ciencia está de acuerdo con ella? — Porque incluso aquellos que saben poco sobre ciencia tienen hoy la sensación predominante de que la ciencia tiene razón, y si la ciencia dice que la antroposofía es una tontería, entonces debe tener razón. Como dije, la gente no necesita saber mucho sobre ciencia, porque después de todo, ¿qué saben los hablantes monistas sobre ciencia? Por regla general, tienen en mente las cosas generales que se aplicaban hace tres décadas. Pero actúan como si estuvieran hablando desde el espíritu completo de la ciencia contemporánea. Es por eso que muchas personas lo ven como una autoridad.

También se puede ver en el destino interior de Brentano el destino exterior, no el destino interior de la visión antroposófica del mundo, sino su destino exterior.

Traducción pendiente de revisión

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario